Senior Writer Bradley S. Klein recently visited Japan's leading golf courses prior to the upcoming PGA Tour and LPGA events as well as the Rugby World Cup and 2020 Olympic Games.

MIKI, JAPAN - Hirono Golf Club, Japan’s most widely heralded course and with good reason called the Pine Valley of the country, is getting a major retrofit. Credit for that goes to Martin Ebert, the British-based course designer who is also the mastermind behind the two new holes at Royal Portrush's Dunluce Course in Northern Ireland, home of the 2019 British Open.

Ebert is no newcomer to major course renovations. He and design partner Tom Mackenzie have a good chunk of the Open Championship rota in their current portfolio, including Turnberry, Carnoustie. Royal Troon, St. George’s and Royal Liverpool. This in addition to dozens of projects new and under renovation, undertaken first when they worked for Donald Steel and, since 2005, on their own.

At Hirono, the meticulous effort at reconstructing Japan’s landmark course took months of study, archive work and drone footage, culminating in a 278-page “Historic Study and Course MasterPlan” that repays close study in its own right, let alone serving as a blueprint for restoration.

The course sits 17 miles northwest and inland of the port city of Kobe, which, with 1.5 million inhabitants, is Japan’s sixth largest city. On a map Kobe looks far from Tokyo, but the 325 mile journey takes a mere three hours and ten minutes thanks to the speedy dependability of the country’s legendary “Shinkansen” bullet train.

Hirono occupies 300 acres of ideally rolling, sandy terrain, with 130 feet of elevation change across the site, interspersed with dense tree cover and framed on the west side by a series of lakes and reservoirs.

The course resulted from a famous design visit to Japan by Englishman Charles H. Alison (1883-1952). Having mastered parkland and heathland design through an extended affiliation with Harry S. Colt, Alison turned himself loose during a whirlwind tour of Japan from December 1930 through February 1931. The ensuing transformation of the country’s approach to golf architecture was akin to the revolutionary influence Alister MacKenzie had on Australia during his two-month design visit in 1926.

The ostensible reason for Alison’s visit was to create a new Tokyo Golf Club – a course that proved to be short-lived, lasting only from 1932 to 1941. But two other commissions he picked up along the way remain powerful examples of the influence that British-trained classical architecture has enjoyed worldwide. Kawana Hotel's Fuji Course is an unparalleled example of oceanfront drama. Hirono, by contrast, makes powerful use of ravines, hillocks, lakes and dense pockets of woodland.

Alison walked the site, then retired to a hotel in Kobe where he pored over a topographic map for a week before coming up with a detailed plan: routing, fairway contours, greens and bunkers. He handed over the plan to two dedicated Japanese enthusiasts who dutifully carried it out: golf writer Chozo Ito and Seiichi Takahata, who was a well-traveled businessman, serious student of design and secretary of the Japanese Golf Association.

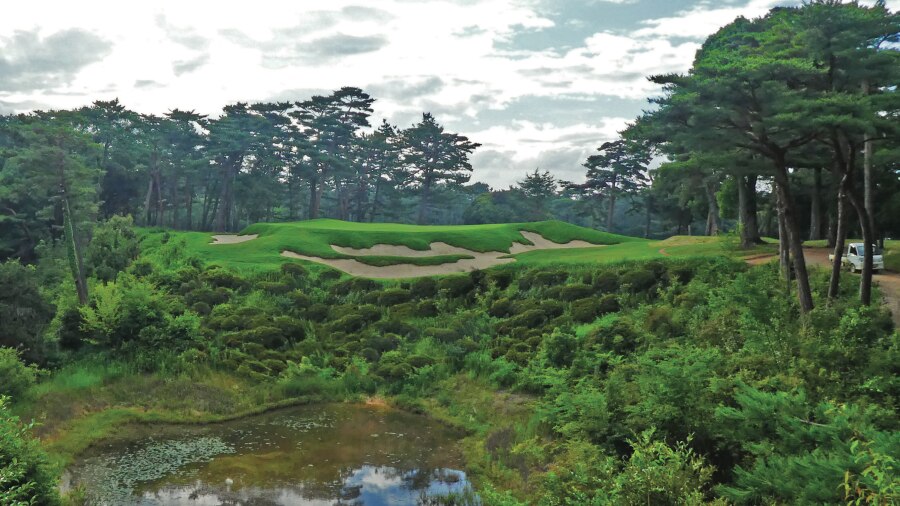

Hirono’s routing made dramatic use of the site’s natural ravines by using them as diagonal features that created strategy and a sense of drama. The course sported Alison’s trademark regard for deep, sprawling bunkers – some of them bigger than the greens they guarded. He was a big proponent of “irregularizing” the bunker edges – making them look choppy, partially eroded and natural. It was a look that evoked Pine Valley, Garden City Golf Club and the National Golf Links of America, all of which Alison knew well.

Alison had previously written dismissively of water hazards. But as Ebert suggests in his report on Hirono, Alison seems to have been influenced by his tours of Japanese gardens. Hirono brings water in play on six holes, though only on two famous par 3s, the fifth and 13th holes, is a forced carry required.

Golf in Japan podcast: Klein on the culture, history and courses you can play leading up to 2020 Olympics

Hirono opened for play in June 1932 to rave reviews. Sadly, Alison never saw his masterpiece. Nor did he ever get the opportunity to do anything equivalent. The Great Depression, war and postwar recovery took their toll on the golf design market worldwide. His career languished.

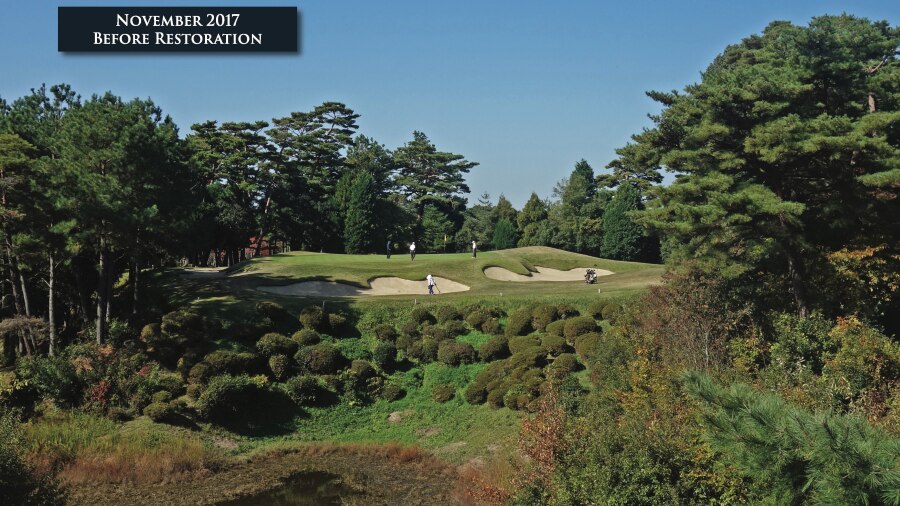

Over many decades, Hirono changed in look – trees grew in, the fairways narrowed considerably, and the greens shrank by one-third, from an original size of 7,380 square feet down to 4,900. Yet the placement of bunkering remained intact, as did the routing sequence with one exception: the lengthening of the 12th hole from a par 4 to a par 5 by the addition of a new green 100 yards farther back.

Unlike most Japanese courses, which sport side-by-side "summer" and "winter" greens, Hirono was designed with one set of greens that functioned adequately year round in the moderate inland climate north of Kobe. But suring a conversion in 1988 from kikuyu to bentgrass, the greens, which had already shrunk, also were changed in their contouring.

Ebert’s plan is to go back as much as possible to the original scale of Alison’s Hirono with respect to fairway widths, bunkering, tree coverage, green size and shapes. The greens reconstruction includes re-grassing with a high-performance bentgrass blend (of 007 and 777) called SuperSeven. The course is also getting an expanded practice range and short-game area.

Work of that scope required a shutdown of the course, with work beginning Jan. 4 of this year and a reopening anticipated in mid-October.

While the tree corridors have been peeled back to reclaim long-range views that had been lost, Hirono retains its character as a wooded layout. In a concession to modernity, the course is getting lengthened by as much as the site will allow – 100 yards – up to 7,275 yards, par 72. The course is also getting shortened up front by 800 yards, to be able to play at 4,916 yards from the forward tees.

Hirono’s excellence in terms of shotmaking options and the character of its native landforms was evident during a mid-June walk through of the property. The natural valley across the fairway of the long par 5 15th hole makes for Alison’s version of Hell’s Half Acre on the second shot. The hole’s name, “Ichi no Tani,” refers to a nearby narrow parcel of hillside that was site of a decisive battle in the Genpei War of 1180-1185.

When it comes to a set of par 3s, Hirono’s are unsurpassed in Japan, if not the world. Gnarly bunkers look like they are eating their way out of the front of the green on the slightly uphill, 170-yard fifth hole (“Fiord”). And all of the “irregularized” influence of Pine Valley is on display on the seventh hole (“Devil’s Divot”).

Ebert’s work has only been possible through the mining of various records to produce a meticulously documented account of how the course evolved. Each hole and each feature has been traced through, thanks to the clarity of Alison’s original plans and the availability of aerial images on a consistent basis since 1948. The result, when Hirono reopens this fall, will be a major landmark of Alison’s work and the most exhaustively restored project of the classic design era that Japan has ever seen.

Though a very private club, Hirono has been willing to open its doors selectively to overseas guests keen on a study of one of the game’s great tracts. For anyone who cherishes the history of golf architecture, an inquiry is worthwhile:

Hirono Golf Club

7 Chome Shijimicho Hirono

Miki

Hyogo 673-0541

Japan